【附錄二】

從朱元璋毛澤東非主權在民式反殖官主義的失敗, 看中國治理範式轉型的必然要求 Viewing the Inevitable Requirement of China's Governance Paradigm Shift from the Failure of Zhu Yuanzhang and Mao Zedong's Non-Sovereignty-in-the-People Anti-Colonial Officialism Archer Hong Qian 中國歷史上有一個帝王制一個黨國制政權,試圖反殖官主義,一個是真的苦寒出身的朱元璋,一個是知識官人毛澤東,但他們都失敗了。因為他們自己就被權力腐蝕了,當然沒有“主權在民實施憲政”的真性情,照樣掉進了“反孔尊孔陷阱”“黃宗羲陷阱”“黃炎培陷阱”,結果都遭遇了殖官主義反噬。此篇綜述透過對朱、毛失敗的深度剖析,論證了“非主權在民憲政”治理模式的不可持續性,旨在為《論殖官主義》提出的“共生治理”方案提供歷史坐標。

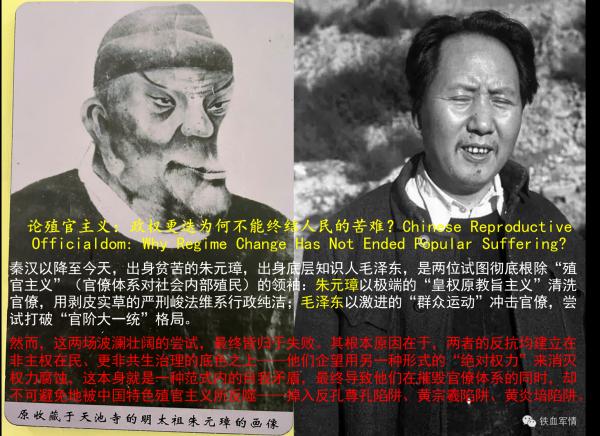

一、 歷史的宿命:非主權在民式反抗的邏輯盲點 在中國歷史的漫長進程中,朱元璋與毛澤東是兩位試圖徹底根除“殖官主義”(官僚體系對社會的內部殖民)的領袖。一位出身貧苦,一位身為底層知識分子,他們對盤剝百姓、虛化主權的官僚階層有着深刻的仇恨: 朱元璋:試圖以極端的“皇權原教旨主義”清洗官僚,用剝皮實草的嚴刑峻法維繫行政純潔。 毛澤東:則試圖以激進的“群眾運動”衝擊官僚,追求一種大鳴大放式的、打破科層制的社會格局。 然而,這兩場波瀾壯闊的嘗試最終皆歸於失敗。其根本原因在於,兩者的反抗均建立在“非主權在民”的底色之上——他們試圖用另一種形式的“絕對權力”來消滅權力腐蝕,這本身就是一種範式內的自我矛盾,最終導致他們在試圖摧毀官僚體系的同時,卻不可避免地被這套體系所反噬。 二、 三大陷阱的鎖死:殖官主義的反噬機制 由於缺乏“主權在民”的真性情與法治架構,朱、毛政權最終都未能逃脫中國治理邏輯中的三大惡性循環: “反孔尊孔陷阱”:當“非主權在民”的統治者(從王權到黨權)試圖穩定秩序時,必然會從早期的“反對舊傳統(反孔)”回歸到利用“等級倫理(尊孔)”,重新依靠官僚體系來維持統治,從而導致殖官主義在倫理支撐下死灰復燃。 “黃宗羲陷阱”:缺乏受治者(人民)直接授權與監督的行政改革,最終都會被官僚體系中飽私囊。朱、毛的改革雖然初衷利民,但在信息壟斷的殖官架構下,反而增加了社會的運行成本與生存壓力。 “黃炎培陷阱”:即歷史周期率。在非主權在民的範式下,領袖的強力干預只能帶來短暫的淨化;一旦強力消退,官僚集團必然進行“制度性修復”,重新確立其作為內部殖民者的權力租金。

三大陷阱一旦重合,殖官主義本身就必然會陷入失序和混亂,這就是熵增效應在宗法家國里的表現,如果沒有被壓制邊緣化的社會自組織漲落,或制度外部性(能量)的輸入,殖官主義賴以寄生的整個體制機制就進入臨界狀態而崩潰。 三、 治理範式轉型:從“內部殖民”到“共生治理”的必然要求 《論殖官主義》核心論點強調,朱、毛的失敗昭示了:單純的治理效能提升或政治動員或反腐倡廉,都已走入死胡同,必須進行從底層邏輯出發的範式轉型: 殖官主義的反噬:官僚體系不僅是管理工具,更是一個具有擴張性的、壟斷價值的獨立主體。在非主權在民的狀態下,它會自動將權力轉化(熵增)為對社會的“殖民資產”,讓社會喪失自組織連接力人。 主權在民的實體化:範式轉型的核心在於“主權”的真正歸屬。必須從“代理人主權”轉向人民“本體主權”,即權力的合法性、解釋權與監督權必須回歸每一位公民,激發社會自組織連接力量。 “孞烎(真誠與透明)”的技術治理:利用透明的價值承兌系統與信用體系取代官僚組織系統(TRUST)對信息的壟斷,從技術倫理——"人藝智能(AI)-生命形態(LIFE)-愛之智慧孞態網(Amorsophia MindsFeild/Network,AM)”——減熵獎抑機制,消解“殖官主義”帶來的混亂與失序,進入“共生治理”的新秩序。利用透明的價值承兌系統與信用體系,取代官僚對資源信息的壟斷,從技術維度消解“殖官”的生存空間,進入共生治理模式。 四、 現實路徑與文明協同:川普賬戶的符號啟示 通過分析《附錄:殖官主義、政治正確、共生治理及川普賬戶》,我們可以看到: 解構官僚中間商:現代政治(無論東西方)正遭遇官僚體系利用“政治正確”進行的隱形殖民。川普賬戶代表了一種“去中間化”的嘗試,即主權者與代議制領導人直接交互,繞過官僚體系的過濾與解構。 賦能與降本:轉型的目標是實現共生治理,通過降低衣食住行學養醫保等基礎生活成本,將新生代和社會從“生存焦慮”中解放出來,轉向生命自組織連接平衡的新文明建構。 五、 結論:走出循環的唯一出口 朱元璋與毛澤東的歷史悲劇證明:如果不確立“主權在民”的真性情,任何反官僚的努力最終都會演變成一場新的官僚殖民。 中國治理範式的轉型不再是可選項,而是歷史的必然要求。這要求我們跳出“打江山、坐江山”的權力存量邏輯,轉向基於交互主體性、真誠與透明的全息共生治理體系。唯有如此,才能真正打破殖官主義的反噬,實現中華文明乃至全球現代性的範式躍遷。

最後,做一個小小澄清 中國知名經濟學家趙曉博士看到《論殖官主義》的內容提要後問我:對“反孔尊孔陷阱”“黃宗羲陷阱”“黃炎培陷阱”,為什麼使用“中國特色殖官主義”解釋,用“王權專制”的解釋力不是更強嗎?而且,他認為“毛可不是反官,他是現代極權:秦始皇+馬克思!他用自己的官反對手的官”。我作如是答: “王權專制”是舊概念,放入殖官主義語境中,就不難發現:“王權”與“黨權”的底層邏輯都是殖官主義。是的,傳統政治學慣用“王權專制”來界定舊體制,但這一概念已不足以解釋官僚體系那種根深蒂固、如病毒般自我複製的頑劣性。 而且,從王權到黨權,本質上是殖官主義的不同發展階段。王權專制時期,官僚體系尚受制於“一姓江山”的長期維護成本,百姓負擔相對較輕,故能維持數百年的長周期循環。黨權專制,是殖官主義的極致演化。它將官僚對社會的滲透與榨取推向極限,導致治理成本激增——我曾在2014年與美籍中共黨史專家馮勝平討論過“黨主立憲”社會成本遠遠高於“君主立君”社會成本的問題,我2003年在給人民日報副總編的信中提出最好成本最低的政體,是“社會元勛立憲制”(重建中國社會自組織力、重建人民共和國中功勳人物立憲)。其中兩組討論通訊被美國之音前主持人陳小平發到網上。 毛氏集團建立起來的“半中半蘇式”體制到“文革後期”面臨崩塌,沒有鄧氏集團“制度外部性”(對美國開放)及相對配套的“熵減改革”續命,早就脆斷。然而,鄧氏集團搞的“半管制半市場”(始於1984,定型於1992),到1990年代末期,就已經造成中國的“世紀之痛”(國企改制剝離勞工經營者持股、基建爛尾、產能過剩、資本過剩、勞工過剩),中國政治經濟出現嚴重“結構性失衡”(胡溫上位稱之為“跛足改革”)。幸得江朱不顧一切加入WTO(世貿組織,還是引入制度外部性),結果,僅在頭十年(2001-2011),殖官主義不但續了命,而且賺取了經濟全球化的紅利,成為GDP世界老二,PPP世界第一。 然而,要命的是,殖官主義者忘乎所以,結構性失衡似乎可以永遠埋在地毯底下視而不見,反以為這是什麼“制度優勢”,開始自我膨脹,完全無視這種經濟全球化紅利,並沒有惠及中國底層人民的嚴峻事實。2020年李克強在“兩會”中外記者招待會上,引用北京師範大學中國收入分配研究院(CHIPs課題組)基於2019年樣本數據,直言不諱:中國有6億人月收入不足1000元(具體為月收入低於1090元的人群,約占總人口的42.8%)。其實還有他沒說的部分:2021年北師大CHIPs課題組更新的數據顯示:月收入在2000元以下的人口約為9.64億;高收入人群極低:根據該課題組研究,月收入超過1萬元的人群占全國人口比例不足1%——中國公民和社會自組織成長,依然被殖官主義牢牢遏制着! 其實,早在2011年“兩會”期間,全國人大法工委副主任、前中紀委副書記劉錫榮就民生問題接受記者訪談時說了四個字:“官滿為患”!而他只是把13年前(1998)中組部部長張全景接受《瞭望周刊》訪談時說出的“官多為患”,由“多”改為“滿”。可以說,張全景、劉錫榮說“憂患”,與王權專制幾乎沒有關係。 誠然,“當國內內殖化榨取接近極限時,官僚體系通過全球化尋求外部市場,是必然之舉”。但是,當殖官主義外溢效應,一再顯現為變相對外殖官:資本產能輸出並非市場競爭,而是官僚意志延伸(如出口補貼、外匯管制、匯率操縱、知識產權竊取),加之偽民族主義包裝下輸出不透明契約和榨取型模式(如資源換項目、債務陷阱),試圖將世界轉化為再生產場域,開始讓世人感到某種統治世界的帝國政治企圖時,這種“外向殖民”式殖官主義的“外溢極限”,就顯現出來,並必然引發國際社會免疫反應和反噬:美西方國家的技術封鎖、供應鏈脫鈎、金融制裁,以及發展中國家的債務重組要求,使外部紅利漸趨枯竭,無法調和的衝突加劇(如中美貿易戰、科技戰)。最終導致殖官主義被迫回歸內卷。 至於個人如朱元璋、毛澤東及後來的接替者,是不是極權專制,並不影響殖官主義的存在!

順便說一句,殖官主義的存在,也不影響中國“知識官人”們的理性自信,所以,我們清楚地看到,曾受我們尊敬的中國精英們(多數是認識的朋友)以及歐美所謂左派媒體,乃至眾多經濟學家,習慣於固守在殖官體系提供的規則範式內進行“理性批判”,卻對川普先生那種直接訴諸人民主權、打破官僚中介“雁過拔毛”式的真情實意和政策實踐,感到恐懼和排斥,他們無法理解川普新政本質上是一場真正的、針對現代殖官體系的“去內殖民運動”,所以,近乎本能地用將川普對官僚建制派(Deep State/代議制下殖官主義的變種)的衝擊,誤讀為傳統意義上的“王權回歸”或“專制復辟”(竟有什麼“反國王遊行”),這就完全是脫離實際,不得要領,可謂認知偏蔽,集體翻車。由此可見,如果看不透“殖官主義”這個為害社會生活的本體,人類治理將永遠在不同的專制形式間輪迴。所以,必須棄用陳舊的“王權”話語,正視“黨權”(如美國民主黨也已經變得面目全非)作為殖官主義極限形式的垂死掙扎。

Viewing the Inevitable Requirement of China's Governance Paradigm Shift from the Failure of Zhu Yuanzhang and Mao Zedong's Non-Sovereignty-in-the-People Anti-Colonial Officialism Historically, there were two regimes that attempted to oppose colonial officialism. One was Zhu Yuanzhang, who truly came from a background of bitter hardship, and the other was Mao Zedong, a scholar official. But they both failed because they themselves were corrupted by power. Lacking the true disposition of “sovereignty in the people and implementing constitutionalism,” they still fell into the “anti-Confucian yet honoring Confucianism trap,” the “Huang Zongxi trap,” and the “Huang Yanpei trap,” ultimately suffering a backlash from colonial officialism. This review, through a deep analysis of the failures of Zhu and Mao, argues for the unsustainability of the “non-sovereignty-in-the-people constitutionalism” governance model, aiming to provide historical coordinates for the “symbiotic governance” solution proposed in “On Colonial Officialism”. I. The Fate of History: The Logical Blind Spot of Non-Sovereignty-in-the-People Style Resistance Throughout the long process of Chinese history, Zhu Yuanzhang and Mao Zedong were two leaders who attempted to thoroughly eradicate “colonial officialism” (the internal colonization of society by the bureaucracy). One came from poverty, the other was an intellectual from the lower strata, both harboring a deep hatred for the official class that exploited the people and diluted sovereignty: Zhu Yuanzhang attempted to cleanse the bureaucracy with extreme “imperial fundamentalism,” using harsh laws like skinning and stuffing with straw to maintain administrative purity. Mao Zedong attempted to impact the bureaucracy with radical “mass movements,” pursuing a social pattern of “four big freedoms” and breaking the hierarchy.

However, both of these grand attempts ultimately ended in failure. The fundamental reason lies in the fact that their resistance was based on a background of “non-sovereignty-in-the-people”—they attempted to use another form of “absolute power” to eliminate power corruption, which itself is an internal contradiction within the paradigm, ultimately leading them to be inevitably backlash by the very system they tried to destroy while attempting to destroy the bureaucracy.

II. The Lock-in of Three Traps: The Backlash Mechanisms of Reproductive OfficialdomOwing to the absence of a genuine commitment to popular sovereignty and a corresponding constitutional–legal framework, both the Zhu Yuanzhang and Mao Zedong regimes ultimately failed to escape three malignant cycles embedded in China’s governance logic: The “Anti-Confucian–Pro-Confucian Trap.”

When rulers operating under non–popular-sovereignty conditions (from royal power to party power) attempt to stabilize order, they inevitably shift from an early phase of rejecting old traditions (“anti-Confucianism”) back to the instrumental use of hierarchical ethics (“pro-Confucianism”). In doing so, they once again rely on the bureaucratic system to sustain rule, enabling reproductive officialdom to revive under renewed ethical justification. The “Huang Zongxi Trap.”

Administrative reforms that lack direct authorization and oversight by the governed (the people) are ultimately captured by the bureaucratic apparatus for private gain. Although the reforms initiated by Zhu and Mao were originally intended to benefit the populace, under a reproductive-officialdom structure characterized by information monopoly, they instead increased social operating costs and intensified pressures on everyday survival. The “Huang Yanpei Trap.”

This is the well-known problem of the historical cycle. Within a non–popular-sovereignty paradigm, strong personal intervention by a leader can produce only temporary purification. Once such force recedes, bureaucratic groups inevitably carry out “institutional repair,” re-establishing their rent-seeking power as internal colonizers. When these three traps converge, reproductive officialdom is destined to descend into disorder and chaos. This constitutes the manifestation of entropy increase within a patriarchal family–state structure. Without the fluctuations of social self-organization that have been suppressed and marginalized, or without the input of institutional externalities (energy), the entire institutional system upon which reproductive officialdom depends enters a critical state and ultimately collapses.

III. Paradigm Shift in Governance: The Structural Necessity of Moving from “Internal Colonization” to Symbiotic GovernanceThe core argument of On Reproductive Officialdom emphasizes that the failures of Zhu and Mao reveal a fundamental conclusion: mere improvements in governance efficiency, political mobilization, or anti-corruption campaigns have all reached dead ends. What is required instead is a paradigm shift grounded in foundational logic: The Backlash of Reproductive Officialdom.

The bureaucratic system is not merely a managerial instrument, but an independent entity with expansive tendencies and monopolistic control over value. Under conditions where popular sovereignty is absent, it automatically converts power (through entropy increase) into “colonial assets” extracted from society. The Materialization of Popular Sovereignty.

The core of paradigm transformation lies in the true ownership of sovereignty. Governance must move from delegated or proxy sovereignty toward the people’s ontological sovereignty, whereby the legitimacy of power, the authority of interpretation, and the right of oversight return to every citizen, thereby activating social self-organizing connectivity. Technological Governance Based on “Xin–Yan” (Sincerity and Transparency).

By employing transparent value-settlement systems and credit infrastructures to replace bureaucratic organizational systems (TRUST) that monopolize information, a techno-ethical framework—Artificial–Artistic Intelligence (AI) – LIFE – the Amorsophia Minds Field/Network (AM)—can implement entropy-reducing incentive and restraint mechanisms. Through this process, the disorder and chaos generated by reproductive officialdom are neutralized, opening the way toward a new order of Symbiotic Governance. IV. Realistic Path and Civilization Synergy: The Symbolic Revelation of the Trump Account Through analyzing “Appendix: Colonial Officialism, Political Correctness, Symbiotic Governance, and the Trump Account,” we can see: Deconstructing bureaucratic intermediaries: Modern politics (both East and West) is facing the invisible colonization carried out by the bureaucracy using “political correctness.” The Trump account represents an attempt at “disintermediation,” where the sovereign and the leader interact directly, bypassing the bureaucracy's filtering and deconstruction. Empowerment and cost reduction: The goal of the transformation is to achieve symbiotic governance, by reducing basic living costs (clothing, food, housing, transportation, education, healthcare, insurance), liberating the new generation and society from “survival anxiety,” and turning towards “civilization synergy.”

V. Conclusion: The Only Exit from the Cycle The historical tragedies of Zhu Yuanzhang and Mao Zedong prove: If the true disposition of “sovereignty in the people” is not established, any anti-bureaucratic efforts will ultimately evolve into a new bureaucratic colonization. The transformation of China's governance paradigm is not just an option, but a historical necessity. This requires us to leap out of the power stock logic of “conquering the country and sitting on the country,” and move towards a holistic symbiotic governance system based on intersubjectivity, sincerity, and transparency. Only in this way can we truly break the backlash of colonial officialism and achieve the paradigm shift of Chinese civilization and even global modernity. AI responses may include mistakes. Current limitations only allow part of the document to be used for this answer. Learn more

Finally, a Brief ClarificationAfter reading the abstract of On Reproductive Officialdom, Dr. Zhao Xiao, a well-known Chinese economist, raised a question. He asked why phenomena such as the “anti-Confucian–pro-Confucian trap,” the “Huang Zongxi trap,” and the “Huang Yanpei trap” should be explained through the concept of *“Chinese-style Reproductive Officialdom.” Would not the explanatory power of “autocratic royal power” be stronger? He further argued that “Mao was not anti-bureaucratic at all; he was a modern totalitarian—Qin Shi Huang plus Marx! He used his own officials to fight against the officials of his rivals.” My response was as follows.

“Autocratic royal power” is an old concept. Once it is placed within the analytical framework of reproductive officialdom, it becomes evident that the underlying logic of both royal power and party power is essentially the same: reproductive officialdom. Indeed, traditional political science has long relied on “royal autocracy” to characterize premodern regimes. However, this concept is no longer sufficient to explain the deep-rooted, virus-like self-replicating resilience of bureaucratic systems. Moreover, the transition from royal power to party power represents, in essence, different stages in the development of reproductive officialdom. Under royal autocracy, the bureaucratic system was still constrained by the long-term maintenance costs of “a polity ruled by a single family name,” and the burden imposed on the population was relatively lighter. This is why such systems were able to sustain long cyclical stability over several centuries. Party-state autocracy, by contrast, constitutes the extreme evolution of reproductive officialdom. It pushes bureaucratic penetration and extraction of society to their limits, resulting in a sharp escalation of governance costs. As early as 2014, I discussed with Feng Shengping, a U.S.-based expert on the Chinese Communist Party, the issue that the social costs of “party-led constitutionalism” are far higher than those of “monarch-led statehood.” Even earlier, in 2003, in a letter to a deputy editor-in-chief of People’s Daily, I argued that the lowest-cost and most sustainable political arrangement would be a form of “constitution established by social merit-holders”—that is, a constitutional order centered on rebuilding social self-organizing capacity and constitutionally empowering contributors of genuine civic merit within the People’s Republic. Two sets of correspondence arising from these discussions were later circulated online by Chen Xiaoping, former host of Voice of America.

The “semi-Chinese, semi-Soviet” system established by Mao’s group was already facing collapse by the late Cultural Revolution. Without the institutional externalities introduced by the Deng group—namely, opening to the United States—and the accompanying “reforms” that temporarily sustained it, the system would have snapped much earlier. Yet the Deng-era model of a “half-regulated, half-market” economy (initiated in 1984 and consolidated in 1992) had already, by the late 1990s, generated what may be called China’s “pain of the century”: the stripping of workers’ and managers’ stakes during state-owned enterprise restructuring, unfinished infrastructure projects, chronic overcapacity, excess capital, and surplus labor. China’s political economy entered a state of severe structural imbalance, which the Hu–Wen leadership later described as “limping reform.” It was only because the Jiang–Zhu leadership pushed China’s accession to the WTO at all costs—once again importing institutional externalities—that the system gained a reprieve. During the first decade after accession (2001–2011), reproductive officialdom not only survived but also captured the dividends of economic globalization, rising to second place globally in GDP and first in PPP terms. The fatal problem, however, was that reproductive officialdom became intoxicated with its apparent success. Structural imbalances were swept under the rug and even mistaken for “institutional advantages.” The ruling elite completely ignored the fact that the gains from globalization had not reached China’s grassroots population. In 2020, Premier Li Keqiang publicly acknowledged—citing data from the China Household Income Project (CHIPs) at Beijing Normal University based on 2019 samples—that 600 million people in China earned less than 1,000 yuan per month (more precisely, under 1,090 yuan, accounting for 42.8% of the population). What he did not mention was that updated CHIPs data in 2021 showed approximately 964 million people earning less than 2,000 yuan per month, while high-income groups remained extremely small: fewer than 1% of the population earned more than 10,000 yuan per month. The growth of Chinese citizens and social self-organization thus remained firmly suppressed by reproductive officialdom. In fact, as early as the 2011 “Two Sessions,” Liu Xirong—then Deputy Director of the Legislative Affairs Commission of the National People’s Congress and former Deputy Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection—summed up the livelihood problem in four words: “official saturation as a societal affliction.” He was merely updating an earlier statement made thirteen years before (1998) by Zhang Quanjing, then Minister of the CCP Organization Department, who warned that “too many officials become a public hazard.” The concerns expressed by Zhang and Liu had virtually nothing to do with royal autocracy. Admittedly, when internal extraction through internal colonization approaches its limits, bureaucratic systems inevitably seek external markets through globalization. However, when the outward spillover of reproductive officialdom repeatedly manifests as disguised external colonization—where capital and industrial capacity exports are driven not by market competition but by bureaucratic will (through export subsidies, foreign exchange controls, currency manipulation, and intellectual property theft), and are further wrapped in pseudo-nationalist rhetoric to export opaque contracts and extractive models (such as resource-for-project deals and debt traps)—the attempt to transform the world into a field of bureaucratic reproduction begins to reveal imperial ambitions. At this point, the externalization limit of reproductive officialdom is reached, triggering immune responses and backlash from the international community: technological blockades, supply-chain decoupling, financial sanctions by Western countries, and debt restructuring demands from developing nations. As external dividends dry up, irreconcilable conflicts intensify—most visibly in the U.S.–China trade and technology wars—forcing reproductive officialdom back into inward involution. As for whether individuals such as Zhu Yuanzhang, Mao Zedong, or their successors were personally authoritarian or totalitarian, this has no bearing on the existence of reproductive officialdom itself. Incidentally, the persistence of reproductive officialdom does not undermine the rational self-confidence of China’s knowledge-officials. We therefore see many respected Chinese elites (most of them personal acquaintances), along with so-called left-wing Western media and numerous economists, habitually confining their “rational critiques” within the rule paradigms provided by the reproductive officialdom system. At the same time, they respond with fear and rejection to Donald Trump’s direct appeal to popular sovereignty and his attempt to dismantle the bureaucratic intermediary structures that skim value at every layer. They fail to grasp that Trump’s policies essentially constitute a genuine de–internal-colonization movement targeting the modern reproductive officialdom system. Consequently, they instinctively misinterpret Trump’s challenge to the bureaucratic establishment (the so-called Deep State—a variant of reproductive officialdom under representative systems) as a return to “royal power” or a “restoration of autocracy,” even staging absurd “anti-king protests.” Such readings are entirely detached from reality and reflect collective cognitive failure. This makes one conclusion unavoidable: without penetrating the ontological nature of reproductive officialdom as a force corroding social life, human governance will remain trapped in endless cycles of different authoritarian forms. The obsolete discourse of “royal power” must therefore be abandoned, and the reality of party power as the terminal form of reproductive officialdom struggling in its final phase must be confronted head-on.

|