前些日子家里计算机的monitor坏了,只好用另一个地方的计算机写东西。 那机器上不能装中文软件,就开始用英文写埃及部分。因为是英文,本打算只给自己记记就算了。可再想想,前面德国和以色列的部分已经贴了,这个还是贴上吧,求个完整。 昨天新的monitor到了,埃及的下部分却还没有写好,接下来用英文还是中文还没想好呢。 要是全世界只有一种语言该多好! ____________________________ We went to Egypt after Israel.

If I had to guess, I’d say probably the first introduction of everyone to Egypt is through a picture of the pyramids. Going to Egypt, for us uninitiated anyway, is synonymous to going to see the pyramids. The most famous pyramids are around Cairo. I didn’t know this until I started researching for the trip. I wasn’t totally ignorant, of course; I knew the pyramids were in a huge Egyptian desert. Don’t the pyramids always show up in pictures and movies with a stern looking guy in Arab garb riding high on a camel marching up a sand dune bathed in the glow of the setting sun? Well, that was the sort of image the mention of the pyramids would unfailingly conjure up in my mind anyway. About Cairo my knowledge did not extend far beyond the fact that it was a huge city and that it happened to be the capital of Egypt. I probably would not be able to tell a picture of Cairo from a picture of, say, Istanbul or Karachi. The pyramids and Cairo were not connected in my mind other than that they were both in Egypt and that I would not have the bragging rights for saying I’ve been to Egypt unless I had both of them covered on this trip. It was indeed a pleasant surprise to me, therefore, a surprise offered by Google Map, that the pyramids are literally within feet of Cairo. When we reach Cairo, we reach the pyramids; we could kill two birds with one stone, hands down.

Our cruise ship had two planned stops in Egypt: Port Said and Alexandria. Neither is close to Cairo. As a matter of fact, they and Cairo form almost an equilateral triangle: the land distance between any two of them is just a tad over 200 kilometers.

Our research before the trip told us there wasn’t much to see in Port Said. Port Said is a big city; of course there are things worth seeing there. But there are more things to see in Cairo; there are the pyramids in Cairo. We needed to get to Cairo and didn’t have time for Port Said. Human beings are strange in the sense that they almost always need some excuse for anything. The animals don’t need excuses for anything; just the humans. If someone does something without an excuse, that someone is said to have no conscience. Look at J. R. Smith of the New York Knicks. He shoots whenever he gets the ball, no excuses, and people say he shoots without conscience. We knew there must be things worth seeing in Port Said. But we needed to rush to Cairo. The writings on the internet that said there wasn’t anything to see in Port Said thus served as our excuse to not spend any time there. Human obsession with excuses may be just a mind trick that we play on ourselves in order to avoid regret; regret makes us unhappy; we don’t like to be unhappy. “To make others less happy is a crime. To make ourselves unhappy is where all crime starts.”Roger Ebert should know; the guy made a living out of watching movies!

Writings on the internet by those who had done the route also indicated that most people chose to go to Cairo from Port Said, stay in Cairo overnight and then rejoin the ship in Alexandria the next day. We decided to adopt the same strategy.

As always, we decided not to go with the ship-sponsored excursion, but booked our trip instead with a tourist agency on our own. Ship-sponsored excursions are highway robbery. We went to Aruba on our most recent cruise. Round trip bus fare between the harbor and California Lighthouse at the northern tip of the island, with that most beautiful public beach at the foot of the hill whereupon the lighthouse stands, cost the three of us a grand total of $15. A family of six we got to know on the trip went with the ship-sponsored excursion. They paid a ransom, maybe not a ransom but a lot more than us, just for their transportation to Palm Beach and back; and get this, they also had to pay an extra $20 apiece for entrance to the resort-owned beach. Aruba’s motto is “one happy island”. We know we were one happy family when we were there; we aren’t totally sure that that family was happy when they found out that they got ripped off.

We chose Nile Blue as our travel agent for the Cairo trip based on comments on the internet. To those cruise ship passengers going the Port-Said-to-Cairo-to-Alexandria route, Nile Blue, for similar prices, offers two alternative Cairo excursion plans. The two plans share some major features, such as a tour to the pyramids, visiting the famous Cairo Museum and an optional dinner cruise on the Nile. But they also differ in that one is a bit Islamic-centric, which covers such tourist favorites as the Mohammad Ali Mosque, while the other is Christian-flavored and concentrates instead on Coptic Cairo. We had seen enough Christian culture on our trips to places like Rome, London and Paris. Well, maybe we hadn’t quite seen enough; but we really hadn’t seen any concentration of Islamic culture yet. We had been in Turkey, but our entire stay there was devoted to visiting St. Mary’s little house in the hills, Ephesus and St. John’s Cathedral, none of which had anything remotely to do with Islam. We were going to Egypt; we wanted to see Islam. So we chose Mohammad Ali Mosque over Coptic Cairo.

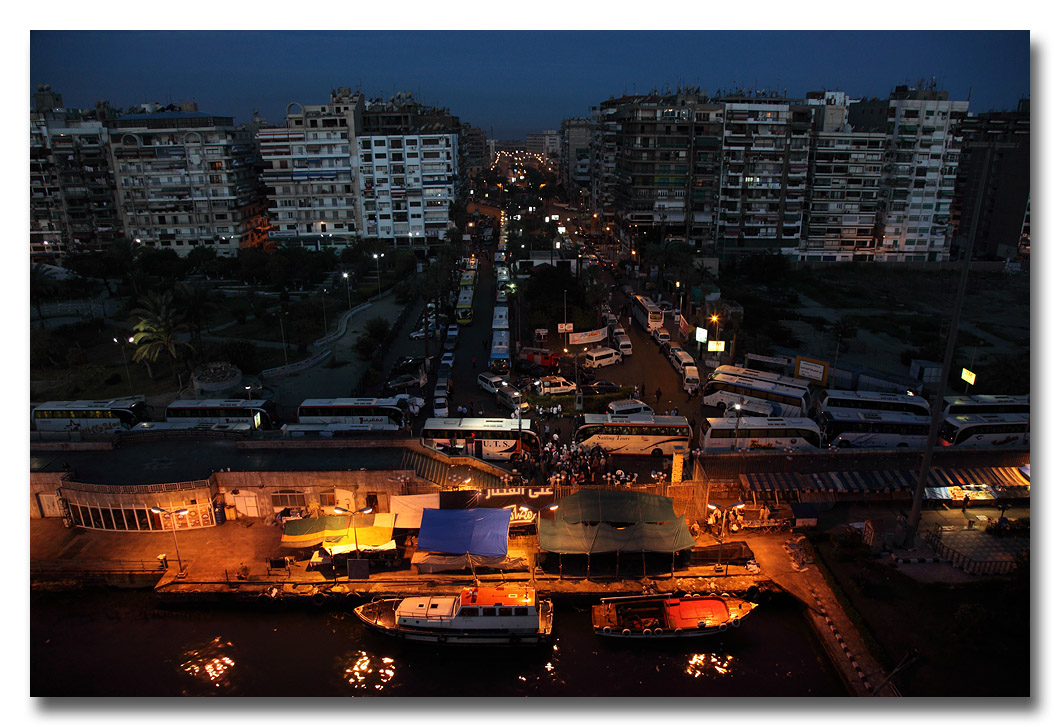

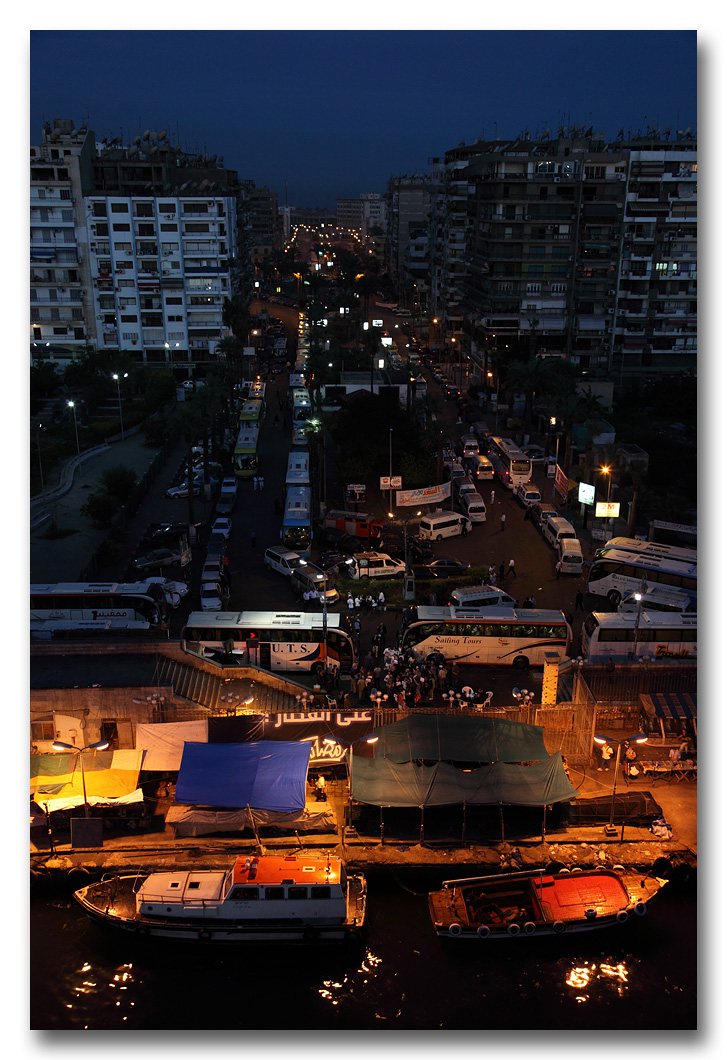

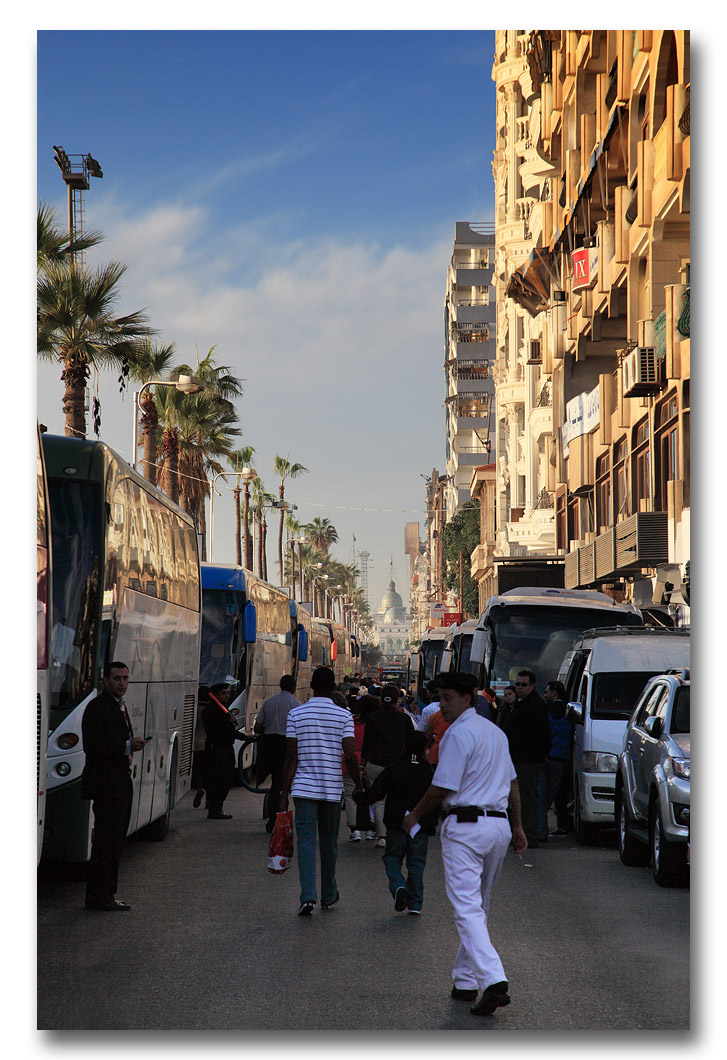

The harbor sprung to life as the Star Princess pulled into Port Said at dawn. An endless line of tour buses were waiting along a narrow street by the pier. Perpendicular to the pier was a thoroughfare stretching far into the heart of the city and beyond. A steady stream of people was being disgorged from the starboard side of our humongous ship and inching its way toward the buses as I stood high above on Deck 15 trying desperately to steady my camera against the tremor sent through the ship by its idling engine and snap a few pictures of my first view of Egypt soaked in the shimmering twilight of morning.

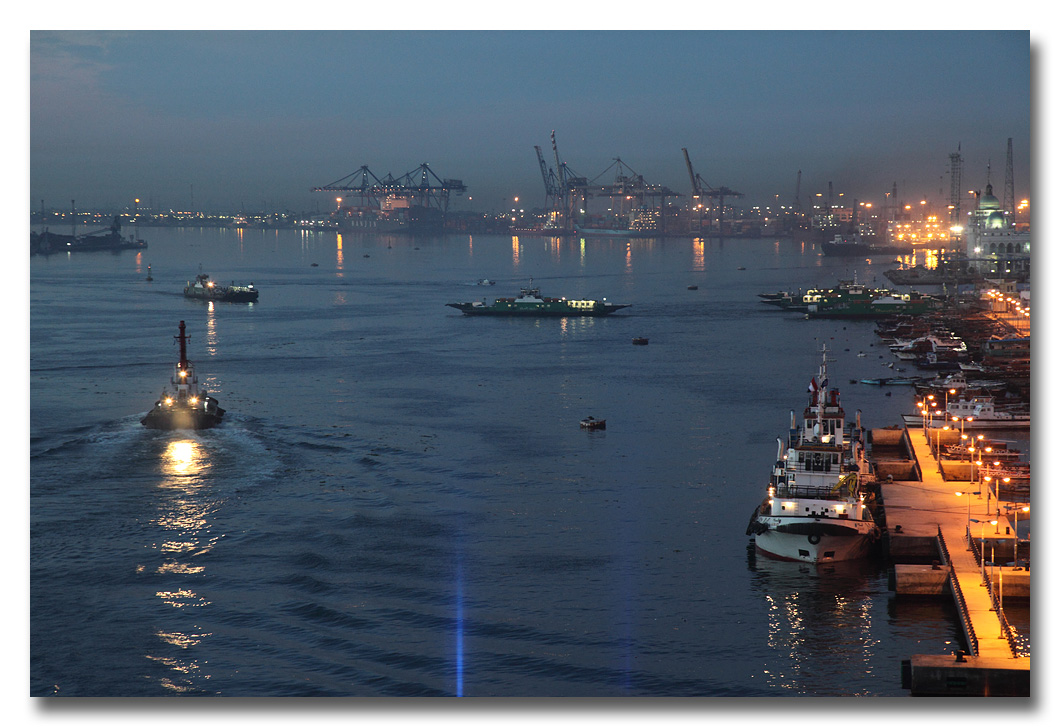

Shrouded by the long shadows of moored gargantuan vessels, little boats of all sorts were toiling around on the rippling surface of dark water.

In the dim halo of street lamps flanking the thoroughfare could be seen police vehicles dotting both sides of the road and people standing by those vehicles kept the surrounding areas under their watchful eyes. Such was my first sight of Egypt, ominous, ghostly, evoking the underworld. I didn’t realize it then, but looking back, that scene of tight security should have alerted me that this was going to be a tour unlike any I had taken before.

We were in no particular hurry, as Blue Nile was supposed to have a minivan waiting down there for us, and as all those countless buses and minivans had to get loaded with tourists first and then organized into a police-guarded convoy for the 3-hour drive to Cairo. Over the years, Islamic terrorists have attacked tourists in Egypt on a number of occasions. The most gruesome attack happened on November 17, 1997, when 62 people, mostly tourists, were killed by terrorists in Luxor. The protected convoy arrangement is in response to such threat.

After finishing a leisurely breakfast, we strolled down to Deck 4, with a piece of luggage each, to disembark. It was fully bright by now.

It did not take us long to find Nile Blue’s minivan parked on the right hand side of the street; it had “Nile Blue” painted on its side panels and a cleanly shaven young man standing by its passenger side door. He looked in his late 20s, with a thick build and a budding beer belly. All smiles, he was sporting a loosely fitting black hoodie and a pair of denim jeans, and was holding up a cardboard sign saying “Nile Blue”.

“My name is Mo’men”, the young man was saying to us as we gathered around him. “It sounds like “moment” in English, so you can call me Moment. It’ll be a while yet before the convoy can leave.” I was just about to tune him out and step away to look around the harbor when he said something that alarmed me: “The drive to Cairo will take a bit over three hours, and we won’t be able to make stops on the way as the convoy must stay together at all times.” More than three hours without stops?! Well, that’s going to be a problem, I thought to myself, a big problem, for my bladder! “So, what if we need to go to the bathroom”? I asked. “Well, you’ll just have to hold your pee”, Mo’men replied matter-of-factly. Here is a bit of hindsight I had after we got to Cairo: if he hadn’t told us there were no planned stops on the way, I might probably have been just fine; now that he had put us on notice, however, I couldn’t help but start dreading what to do when nature called. As a matter of fact, I immediately felt the need to take a leak upon hearing Mo’men’s unpleasant announcement.

Truth be told, I felt a bit put off by Mo’men’s reply. We’ve been to places around the world. No matter where we are, we invariably find people to be accommodating when it comes to tourists’ reasonable, expected needs. It is not uncommon either for people to even go out of their way to offer help. I was taken aback by Mo’men’s response because, just a moment before I popped the question, he had been saying how happy he was to see us and how his personal living as well as the health of the Egyptian economy both heavily depended on tourism. I can’t even chalk it up to inexperience, as Mo’men later revealed that he had been employed in the tourism industry for years, ever since graduation from college. In my urge to rationalize everything, I did manage to find an excuse for Mo’men: our vehicle needed to stay with the convoy at all times for security reasons. But this does not explain why arrangements couldn’t have been made for the entire convoy to make at least one stop somewhere along the way.

Long story short, I went to the bathroom three times during the one hour we waited for departure at the harbor just so I wouldn’t have to cause some embarrassing international incident because I needed to pee.

I did manage to survey the harbor a bit in between. The street the Nile Blue van was parked on was flanked on one side by an endless row of nondescript one-storey buildings housing what looked like warehouses and waterfront stores and on the other side by apartment buildings of different heights and sizes. At the end of the street stood a glistening mosque topped with light green domes, reminding us unequivocally we were in a land of Muslims.

Indeed, most conspicuous amid an assortment of constructions lining the opposite side of the harbor was another majestic mosque, its twin minarets, meticulously sculptured, towering in sharp contrast next to a crowd of colossal portal cranes of ruthless functional design, a mesmerizing ode to history in symphony with a barbarian shout of modernity, beauty and the beast, the two sides of a coin called Egypt. All that’s there left to do is figure out which is the heads' side, and which the tails' side.

The long convoy of buses and vans finally stirred into motion. It was some more time yet before it came our turn to merge into the procession and start the trip through Port Said toward Cairo and the pyramids.

The highway we were traveling on traversed on the eastern edge of the Nile Delta. The surrounding terrain reminded me of the time when we visited Fort Lauderdale, where I stood in awe at the vast and totally flat southern Florida coastal plain, uninterrupted for miles and endless miles, stretching in all directions to the horizon. Unlike the Florida plain, though, the land here was heavily cultivated. Farming communities, all cowering around their own mosques with towering minarets, dotted the right hand side of the highway. A mysterious grayish wall could be seen stretching endlessly along, and keeping a good distance from, the highway on the left side. We drove for the most part on the highway, which was of okay quality at first, but gradually deteriorated to a somewhat rundown condition as we got closer to Cairo’s much heavier traffic. Occasionally, our van veered onto local roads, either for shortcuts or to circumvent pay stations.

It became immediately clear that Mo’men was a well trained tour guide. No sooner had the van started moving than he launched into a nonstop offering of facts and explanations about Egypt in general and about what our van was passing by at any given moment. His narration kept us from nodding off during a few boring stretches of the trip. Of all the information he generously doled out to us, I found most interesting the part about the Suez Canal, which ran side-by-side with our road for the first one-third of our journey.

Suez and Port Said are both coastal towns in Egypt; Suez is on the Red Sea, Port Said overlooks the Mediterranean. While the distance on land between the two is only about 150 km, to travel from one to the other by sea, without the benefit of the canal, one would have to skirt the entire African continent. The first waterway linking the Red Sea to the Mediterranean was created by ancient Egyptians around 2,000 B.C., who dug a canal connecting the Red Sea with the Nile which enters into the Mediterranean. The canal allowed the passage of light sail boats, either pulled along by horses or camels or rowed. Though poorly constructed by today’s standards, it was kept in use for more than a thousand years before it dried out and was silted up by the sand constantly swept around by the great desert winds.

A new canal was contemplated in the 18th century, but the idea was nipped in the bud because there was thought to be a 30-foot difference between the levels of the Red and Mediterranean Seas, which would require the construction of large and costly locks.

Interest in a waterway was rekindled in the 19th century by some Frenchmen. Chief among them was Linant de Bellefonds, who had become chief engineer of Egypt's Public Works. He and Mougel, a hydraulics engineer, surveyed the Isthmus of Suez and planned out a direct line from Suez to Peluse, crossing Lake Timsah and the Bitter Lakes, totaling 147Km in length. For his part, Bourdaloue established that the difference in levels between the two seas was so small as to be negligible.

A French diplomat and engineer, Ferdinand de Lesseps, then convinced the Egyptian viceroy Said Pasha to support the building of a canal. In 1858, the Universal Suez Ship Canal Company was formed and given the right to begin construction of the canal and operate it for 99 years. Construction of the Suez Canal officially began on April 25, 1859. It opened ten years later on November 17, 1869 at a cost of $100 million. Some sources estimate that over 30,000 people were working on the canal at any given period, that altogether more than 1.5 million people from various countries were employed, and that thousands of laborers died on the project. Forced labor of Egyptian workers was even used for a period of time, and this practice of slavery was stopped only due to British objection. One should not be so quick to interpret the British opposition as purely based on humanitarian concerns, though. Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, Britain was in competition, and frequently in conflict, with France in the eastern Mediterranean. The British feared the alterations in the status quo that the Canal apparently would bring. They specifically feared that a canal open to everyone might interfere with its India trade and, therefore, preferred, and eventually built, a connection by train from Alexandria via Cairo to Suez. In truth, the British could not be blamed for being paranoid; Napoleon, after all, had conquered Egypt for exactly that purpose: to undermine Britain's access to its trade interests in India and to establish a French presence in the Middle East, with the ultimate dream of linking with a Muslim enemy of the British in India.

Once Mo’men started his history presentation on the Canal I couldn’t wait to hear him talk about Nasser. Nasser led the 1952 revolution in overthrowing King Farouk. He also led Egypt in resisting the invasion by Britain, France and Israel in 1956 and restoring sole control of the Suez Canal to Egypt, a victory considered to have erased a mark of national humiliation. He adopted many a socialist measure. He practiced authoritarianism. It shouldn’t be hard, therefore, to see a similarity between Nasser and Mao. In a sense, Nasser was to the Egyptians as Mao was to the Chinese during their respective times. Nasser died in 1970. Mo’men is only in his 20s. I thought it would be interesting to see how young people like Mo’men viewed Nasser. A comparative study of some sort may help shed light on why, despite the disasters Mao brought about, he is still worshiped by so many in today’s China.

Mo’men did not disappoint. “Nasser was a hero,” he gushed. “He made mistakes, but he was a hero. He got us back the Canal, if nothing else”, Mo’men continued. It was obvious that Mo’men’s adoration for Nasser was first and foremost based on patriotism. He also compared the Mubarak period with that of Nasser’s, insisting that there wasn’t nearly as much corruption during the latter’s reign.

These, of course, are familiar refrains one hears in connection with Mao. Mao was the one who drove imperialist influence out of China. He was the one who rid the country of corruption. But what about the millions who starved to death due to his brazen communist experiment with agriculture? What about the millions more who perished during his numerous political power plays?

People can debate about Mao till the end of time. To me, the debate is largely fruitless, as a Cartesian pursuit anyway, as the two sides to the debate are fundamentally expressing their diametrically opposed beliefs about human nature. Those who sing sincere praises of George Washington tend to believe human beings can come together by overcoming their prejudices in adopting a set of universal values. Surely we human beings, because of our empathetic nature, are capable of extending our love across racial and national lines. Lauding Mao are those who poo-poo the idea of universal values because of their belief that self-preserving instincts inevitably drive people apart. Even if old George was himself a real saint, most of those who advertise him do so out of selfish nationalistic motives, they figure. These people feel the need for a Chinese hero to go tit for tat versus George worshippers. There is, alas, not one of George’s ilk in the entire history of China. So Mao will have to do. In a struggle over nationalistic interests, Mao’s being Chinese trumps all of his sins, imagined or real.

The pro-Mao and anti-Mao debate is akin to religious debates; triumphs take not rational persuasion but a leap of faith. However, it is much more complicated than religious debates. Empathy and self-preservation are two sides of the coin of human survivability. One can’t exist without the other as each is the extension of the other. The line in between is not only blurred, but it also differs from person to person. When the pro-Mao and anti-Mao debate is viewed as based on this dichotomy of human nature, our animal side versus the human side, dark against bright, it becomes clear that, as much pain as it causes on both sides, the war of words will rage on. But I digress.

Mo’men’s explanation for the mysterious grayish wall finally came when our van passed a monument made out of an old Mig-21 fighter jet standing guard in front of a gate in the wall. “Those are the barracks of the Second Army”, he said simply. “Where is the Third Army?” I asked, half expecting Mo’men to pick up a topic about that army unit, infamous for getting surrounded by the Israelis at Suez during the October War of 1973 but famous for allegedly refusing Mubarak’s order to fire on demonstrators in Tahrir Square. “They are stationed further to the east, more on the Red Sea side”, said Mo’men. “We would have scored a much bigger victory during the Ramadan War but for U.S. support of the Israelis, you know. The Americans are just way too pro-Israel”, Mo’men, head shaking, went on to say. Maybe because we were from the States and were his guests at the moment, and maybe because hatred for American foreign policy in that part of the world is always tinged with a love for American culture and technology, a complex the jeans on Mo’men and the i-Phone in his hands testified loudly to, he did not launch into an anti-US rant, as one might have expected.

Three and a half hours and a dearth of attractive view offered Mo’men the opportunity to cover many topics. We found ourselves in Egypt just when the newly elected Egyptian president, Morsi, was being challenged for being too much of a Islamist in his policies. Mo’men opined that Morsi was a good man and should be given more time to straighten out the country’s affairs. If Mo’men’s narration about Egypt gave us broad hints at his political inclination, his comments on world affairs confirmed our inklings. He announced to us, for example, that 9/11 was no more than a CIA conspiracy and that Obama’s Middle East policies were solely geared toward protecting Israeli interests. I would not explain Mo’men’s being so loose-tongued by our group’s being all Chinese; he knew we all presently lived in the States. In fact, I’m convinced that, intentionally or unintentionally, Mo’men said what he said to influence us, to do a bit of brainwashing, if you will. This was made especially clear when, later on, he gave us a most adulating version of Muhammad Ali’s love life during our visit to the latter’s grand namesake mosque.

Remember Mo’men’s announcement that there wouldn’t be any stop on the way had sent me to the bathroom three times? Well, it turned out that Mo’men wasn’t being truthful: we made a stop on our way to Cairo at a fully functional rest area, when both the driver and Mo’men felt the need to go take a leak. What about the security concerns, about the convoy, you ask? I’ll say more about the traffic condition on Egyptian highways later on; let’s just say for now that the traffic was such that our long snake of a procession was soon dissected and slaughtered by wildly driven beasts of vehicles so that the buses and the vans so neatly woven into the convoy soon had to survive on their own. No sooner did the tour vehicles left the harbor than their drivers started concentrating on threading their own way out of Port Said and stopped paying any attention to keeping the convoy in formation.

|