|

2022-7-23

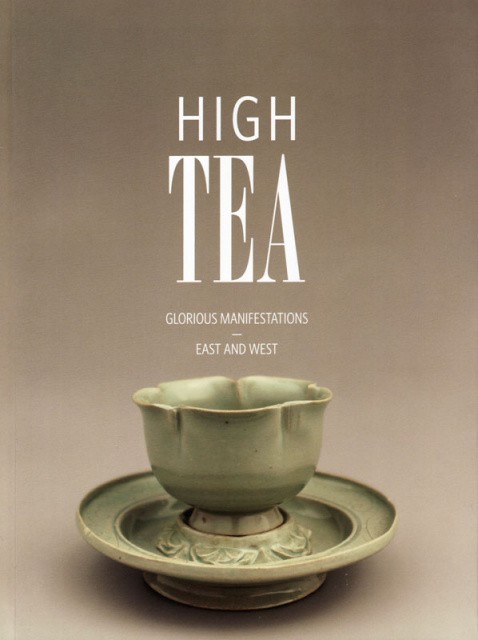

华盛顿美洲国家历史博物馆里,展览有一款德国梅森的白瓷茶壶,非同一般:

因为这一把茶壶,承继有深厚的历史文化淀积。

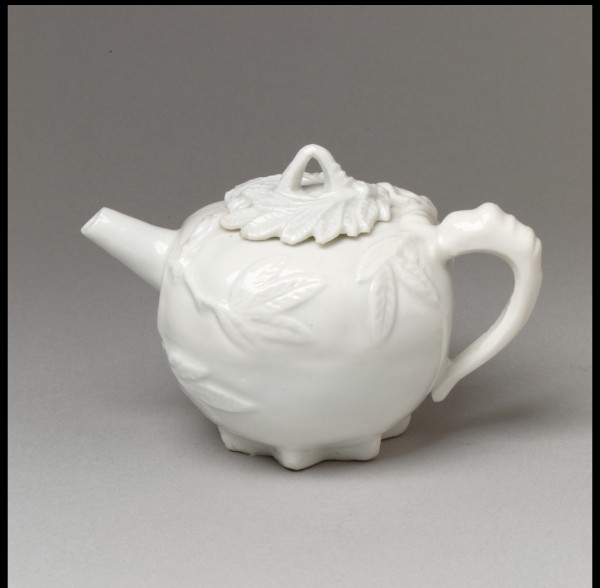

This teapot and cover is from the Smithsonian’s Hans Syz Collection of Meissen Porcelain. Dr. Syz (1894-1991) began his collection in the early years of World War II, when he purchased eighteenth-century Meissen table wares from the Art Exchange run by the New York dealer Adolf Beckhardt (1889-1962). Dr. Syz, a Swiss immigrant to the United States, collected Meissen porcelain while engaged in a professional career in psychiatry and the research of human behavior. He believed that cultural artifacts have an important role to play in enhancing our awareness and understanding of human creativity and its communication among peoples. His collection grew to represent this conviction.

The invention of Meissen porcelain, declared over three hundred years ago early in 1709, was a collective achievement that represents an early modern precursor to industrial chemistry and materials science. The porcelains we see in our museum collections, made in the small town of Meissen in the German States, were the result of an intense period of empirical research. Generally associated with artistic achievement of a high order, Meissen porcelain was also a technological achievement in the development of inorganic, non-metallic materials.

This teapot and cover with a wishbone handle and dragon spout is a later example of items reminiscent of the early Böttger porcelains admired for their raised ornament, and designed originally by the Dresden court goldsmith Johann Jacob Irminger (1635-1724), the so-called Irmingersche Belege. The applied grapevine (Wein-Laub) design seen on this teapot and cover was especially favored.

In the eighteenth century tea, coffee, and chocolate was served in the private apartments of aristocratic women, usually in the company of other women, but also with male admirers and intimates present. In affluent middle-class households tea and coffee drinking was often the occasion for an informal family gathering. Coffee houses were exclusively male establishments and operated as gathering places for a variety of purposes in the interests of commerce, politics, culture, and social pleasure.

几乎是同样制式的梅森白瓷茶壶,在佛罗里达杰克森维尔的Cummer美术园林博物馆里也有一个,曾在西棕榈滩市Norton美术馆的高茶节目中借展过:

同样是这位瑞士移民收藏的同时期的康熙德化窑白瓷茶壶,则捐献给了大都会博物馆。

在设计、造型、色彩和价格上,德国学生都精益求精,一丝不苟,全面超越了中国老师,青出于蓝而胜于蓝,让老师无地自容啊!

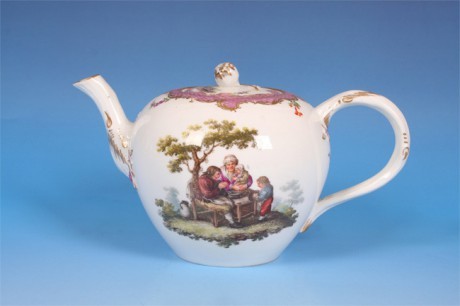

Unexpected events in 1720 accelerated the pursuit of color into one of the most important breakthroughs for the Meissen manufactory, and this was a high priority because it allowed for the application of decorative motifs that were not only durable, but exceptionally rich and luminescent in color quality. From Vienna, the painter Johann Gregor Höroldt (1696-1775) came to Meissen in April 1720 with Samuel Stölzel (1685-1737), a former member of the Meissen team who took the secret of porcelain manufacture to the Imperial capital. Subject to severe punishment for revealing the secret, known as the arcanum, to the Viennese, Stölzel’s pact was to bring the talented Höroldt to Meissen in order to build the color palette and train apprentices in enamel painting. Höroldt organized the laboratory for the production of enamel colors and developed the so-called muffle kiln to fire the enamels onto the surface of the glaze at a gentle temperature of about 1382° F., 750°C. By 1731 a trained company of twenty-nine enamel painters was in place with Höroldt then appointed their director. Höroldt’s objective was to achieve a unity of style in the work of the porcelain painters, and towards this end, he took on young inexperienced painters as apprentices with others more experienced.

This teapot is one example of the porcelains painted in the chinoiserie style developed by Höroldt at Meissen. During the seventeenth century cargoes of exotic goods traded through the Dutch and English East India Companies reached Europe, bringing new colors, images, and tactile sensations into people’s lives. Even if the goods were not affordable to the majority, they were still visible in fashionable city centers where they were marketed.

This teapot is painted in underglaze blue and onglaze enamels with birds in flight over flowering tree peonies and rice straw fences in the Japanese Kakiemon style. The rim of the teapot is encircled with a patterned border in iron-red. The Meissen Manufactory often included gold decoration on items in the Kakiemon style, which was uncommon in the Japanese originals.

Kakiemon is the name given to very white (nigoshida meaning milky-white) finely potted Japanese porcelain made in the Nangawara Valley near the town of Arita in the North-West of the island of Kyushu. The porcelain bears a characteristic style of enamel painting using a palette of translucent colors painted with refined asymmetric designs attributed to a family of painters with the name Kakiemon. In the 1650s, when Chinese porcelain was in short supply due to civil unrest following the fall of the Ming Dynasty to the Manchu in 1644, Arita porcelain was at first exported to Europe through the Dutch East India Company’s base on Deshima (or Dejima) in the Bay of Nagasaki. The Japanese traded Arita porcelain only with Chinese, Korean, and Dutch merchants through the island of Dejima, and the Chinese resold Japanese porcelain to the Dutch in Batavia (present-day Jakarta), to the English and French at the port of Canton (present-day Guangzhou) and Amoy (present day Xiamen). Augustus II, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, obtained Japanese porcelain through his agents operating in Amsterdam who purchased items from Dutch merchants, and from a Dutch dealer in Dresden, Elizabeth Bassetouche.

European flowers began to appear on Meissen porcelain in about 1740 as the demand for Far Eastern patterns became less dominant and more high quality printed sources became available in conjunction with growing interest in the scientific study of flora and fauna. For the earlier style of German flowers (deutsche Blumen) the Meissen painters referred to Johann Wilhelm Weinmann’s publication, the Phytantoza Iconographia (Nuremberg 1737-1745), in which many of the plates were engraved after drawings by the outstanding botanical illustrator Georg Dionys Ehret (1708-1770). The more formally correct German flowers were superseded by mannered flowers (manier Blumen), depicted in a looser and somewhat overblown style based on the work of still-life flower painters and interior designers like Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer (1636-1699) and Louis Tessier (1719?-1781), later referred to as “naturalistic” flowers.

The Seven Years War of 1756-1763 brought Meissen’s production almost to a halt when Saxony was under Prussian occupation. In order to preserve the ‘secrets’ of porcelain manufacture much of the Meissen manufactory’s infrastructure was destroyed. The Saxony economy was severely weakened by the war which brought sales and commissions close to a standstill, and in addition Meissen faced growing competition from enterprises like Sèvres, Wedgwood, and the Thuringian manufactories. This tea and coffee service represents the awkward period of transition as Meissen sought to produce models that would appeal in a different political, cultural, and economic context.

The shapes seen in this service date from before the Seven Years War and the overglaze purple enamel painted subjects are based on prints in the style of Dutch landscape artists like Jan van de Velde II (1593-1641) popular in Meissen products of the 1740s and 1750s. Polychrome flourishes in sea-green, purple, blue, and yellow decorate the handles and finials. The service is outmoded in style at a time when the manufactory was at a low point following the war and the ensuing economic crisis. At the same time Meissen began to replace pre-war designs with those influenced by the French Sèvres porcelain manufactory.

相反,在苏格兰国家博物馆里,则收藏有康熙德化窑的另外一款茶壶:

算是给我们大中华帝国,多少找回一点儿面子。下面这一把,是梅森十九世纪早期的一把花货:

也算是梅森茶壶小试牛刀的第一把。从1709年到-1779年的70年间,梅森茶壶不断花样翻新,琳琅满目,引领世界茶壶的新潮流:

Johann Joachim Kaendler first realized the idea of incrusting porcelain vessels with snowball flowers in May 1739, the first item he created being a teapot covered in snowball flowers with leaves and branches. It was such a revolutionary idea that Frederick II of Prussia ordered numerous vases in design for the Neues Palais in 1762, where they can still be admired in the Fleischfarbenen Kammer to this day.

|

|