| |

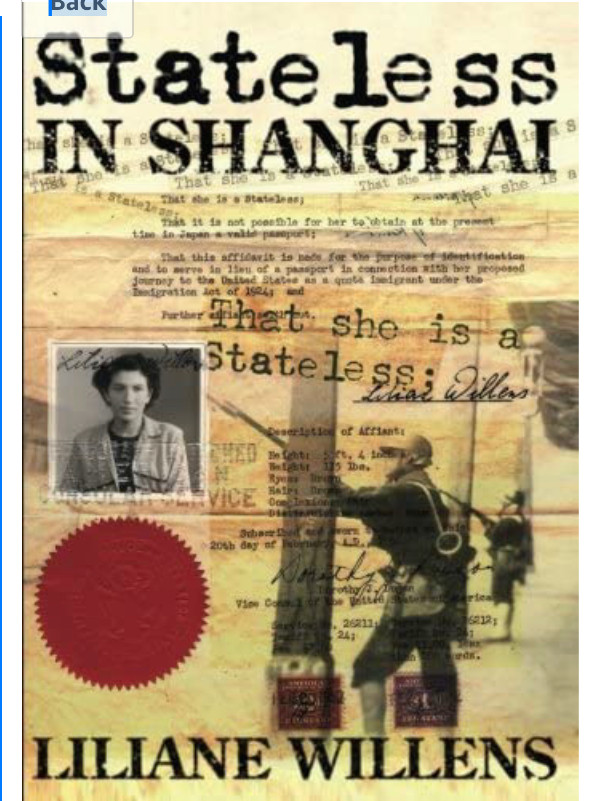

網友:翟東升演講中提到的搞定紐約書店的老太太被中國網友挖出,她就是Liliane Willens。Liliane Willens出生於俄羅斯的猶太人,後來全家在二戰中逃到上海。中共建政後她被中共允許移民到美國,隨後幾十年活躍中美兩國。她的代表作《無國籍者在上海》(下圖)。

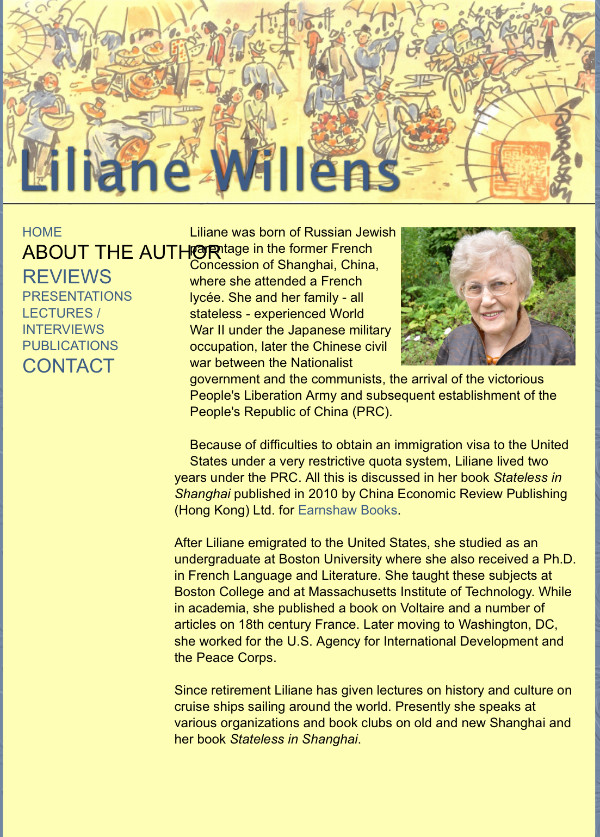

繼續深挖的結果,我發現了更多的關於她的資料。 下圖是她網站上的簡歷:

Liliane Willens 出生於上海的法租界。難怪她的中文講得這樣好。其父母是俄羅斯猶太人,她在那兒讀的是一所法國學校。

她和她的家人-全都是無國籍人士-在日本軍事占領下經歷了第二次世界大戰,和後來的國共內戰。隨後PRC成立。

由於嚴格的配額制度,Liliane難以獲得前往美國的移民簽證,她在中國居住了兩年。 所有這些都在中國經濟評論出版(香港)有限公司於2010年為Earnshaw Books出版的《無國籍者在上海》一書中有講述。

莉莉安娜(Liliane)移居美國後,在波士頓大學攻讀本科,並獲得了法國語言文學專業博士學位。 後來她在波士頓學院和麻省理工學院教授這些課程。 在學術界,她出版過一本有關伏爾泰的書以及一些關於法國18世紀的文章。 後來搬到華盛頓特區,她曾在美國國際和平開發署工作。 退休後,Liliane就在世界各地航行的遊輪上舉辦有關歷史和文化的講座。 目前,她在各個機構和讀書俱樂部做關於新舊上海以及她的《無國籍者在上海》的演講。

(上圖)喬治·華盛頓大學孔子學院舉行Liliane的二十世紀早中期的上海古董家具捐贈儀式。

從介紹和以及照片上看她的穿戴,她的確對中國是有着濃厚的情感的。

看來,這位猶太裔的紅色老太太不是具有華爾街背景啥的,也許她的家人是, 也許是翟東升在吹牛?

下面是她的《無國籍者在上海》那本書的摘錄: Stateless in Shanghai extractby Liliane Willens Old Amah and I became inseparable as I was growing up. She took full

charge of me (“Leelee”) and of my sister Riva whom she called “Leeva”.

She fed, bathed and dressed us in clothes which my mother no longer

sewed but now purchased. My father’s income increased substantially at

the end of 1927 when he was hired as a sales representative for Sun Life

Assurance Company of Canada, a firm headquartered in Montreal. Soon

after, we moved to a larger apartment in a small complex of rental

buildings on Route Ratard (Julu Lu), where my parents got a private room

for Old Amah in the servants’ quarters annex. Socially, our family was

moving up — Old Amah, too, in the eyes of her friends.

Old Amah insisted on getting us soft canvas shoes, explaining to my

mother that leather shoes were “vely no good” for our feet since the

shoelaces would untie quickly and we could fall and hurt ourselves.

Thanks to these soft shoes, I easily could outrun Old Amah, who walked

with a spring in her gait because her feet were very narrow for her tall

build.

My sister Riva hardly ever caused any problems but by the time I was

five years old I was terrorizing the little girls with whom I played in

the garden, fighting with the little boys living in our complex and

sticking out my tongue at the Chinese children in the streets. Old Amah

often saved me from yelling and spanking, calming my mother down by

saying: “When Missee Leelee big, she good like Leeva.” Although I had

already picked up some of the Shanghainese dialect, Old Amah always

spoke to me in Pidgin English, for she understood intuitively that my

parents and other European parents did not want their children to learn

Chinese. There was no need for the foreigners to use it since Chinese

servants were obliged to speak a smattering of their masters’ languages,

whether it was Pidgin English, French, Russian or German.

When I was about six years old, my mother let me accompany Old Amah on

her shopping trips in the streets of “Chinese” Shanghai, a world that I

discovered was very different from my own. I was glad to be away from my

noisy baby sister Jacqueline, a crying “nuisance” who had come into my

life a year earlier. This child, whom all called Jackie, was getting too

much attention from my parents and their friends. They could not decide

whether she resembled her mother or her father but they agreed that she

did not resemble her two older sisters. Riva had my father’s looks and

calm disposition, while I resembled my mother in looks and temperament,

which meant I was a very active child.

On the way to the market, Old Amah and I walked through several very

poor neighborhoods where we would inevitably pass a man slowly pushing a

wide wooden cart. He went in and out of the alleys and lanes, where the

Chinese lived in tenements and hovels without flush toilets, collecting

the buckets of human waste that had accumulated overnight. When this moo dong man

announced his arrival women rushed out with wooden buckets, which he

emptied with a deft arm movement into large wooden containers securely

tied to his cart. When they were filled to the brim he covered them with

wooden lids and then slowly pushed his overloaded cart in the direction

of the nearby countryside where he sold his morning collection to

farmers as fertilizer. During the very humid summer months of July and

August, when the thermometer sometimes hovered near 100 degrees

Fahrenheit, the putrid smell from these carts hung in the air for the

entire morning.

On those trips with Old Amah I watched her bargain endlessly with the

food vendors over the price of rice, noodles, vegetables and fruit. She

became quite theatrical when a price was quoted — she walked away

complaining loudly that the street vendor was trying to rob her. She

soon returned, however, and bargained again; then after much sighing she

agreed grudgingly to buy the items she had earlier examined. She

watched very carefully as the seller weighed her purchases on a scale

consisting of a metal tray attached a stick with a movable weight piece.

On one of our excursions to the market Old Amah became very angry with

me. I did not have time to tell her that I needed to “makee doodoo”, so

while she was talking to a friend at the marketplace I squatted on the

street and defecated in my pants. I was simply doing what small Chinese

children always did when they wanted to “makee doodoo”, except that my

pants were not split on the backside. Old Amah began lamenting that

“Big Missee get vely, vely angly”, and that Leelee “give me walla, walla (trouble, trouble), ah ya, ah ya”.

My proper and demure Old Amah always yanked me away whenever she

noticed a man using a wall as an open-air toilet, while I wondered why

he did not go home and use his bathroom as we did in our house. In my

mind, only small children had the right to relieve themselves in public!

I looked forward to these outings with Old Amah because I knew that

whenever she bought cooked meat, fish or baked dough she would bite off a

small piece and share it with me. While flies were swarming and buzzing

around the open food stalls, I admired the vendors who tried to hit

them with the straw fans they used to fan their charcoal stoves.

Sometimes, when Old Amah had a few extra copper coins to spare, she

bought a piece of tofu fried in sizzling oil which she blew upon before

handing it to me. She would also share with me her breakfast food, the

small da bing pancake and the you tiao, strings of dough

fried in boiling oil and then twirled by the vendor into an elongated

shape. These two oily and very hot food items were wrapped in a piece of

soiled paper torn from a newspaper. When Old Amah was feeling extra

generous she bought and shared with me the pyramid-shaped zongzi filled

with glutinous rice and wrapped in palm leaves, which I munched with

delight. For dessert, which she bought for me when I nagged her

sufficiently, there were the sticky yuan xiao, balls of rice

covered with sesame seeds. I especially enjoyed the Chinese Mid-Autumn

Festival since Old Amah would always buy me a dousha bao, a cake filled with mashed sweet red beans that she knew I preferred to the cakes and sweets we ate at tea time in our home.

Old Amah could never ask to be refunded for the copper coins she spent

on me because my parents would not have allowed her to buy me food made

in such unsanitary conditions. Of course I did not tell my mother about

eating these forbidden delicacies because my trips with Old Amah would

have ended. The food I ate in the marketplace was much tastier than the

meat, chicken, potatoes, vegetables and soup we ate at home, where I was

always told to eat slowly and wipe my mouth with a napkin. My taste for

Chinese food may have been enhanced by the fact that Old Amah and I had

a secret which we hid from my parents.

Whenever I ate food in the street Old Amah had to shoo away beggar

children who had gathered around me watching me intently. I yelled “sheela, sheela”

(“go away”) at them, not realizing they were hungry. I thought it was

silly of them to stare at me while I was eating and wondered why their

mothers did not buy them food. I was annoyed when they surrounded me and

I yelled at them in the Shanghai dialect, borrowing the words they used

to insult me. The fact that Chinese children swore at me — the yang guizi(foreign devil) with her da bizi (big

nose) — did not bother me, for I had already surmised that as a white

person I was superior to them. From a very early age my friends and I

looked down on the Chinese, whose main function we had observed was to

serve us and all other foreigners. Little did I know then we were

behaving as colonial racists did in other parts of the world.Stateless in Shanghai is

the story of Dr. Liliane Willens' experiences growing up as a

"stateless person" in cosmopolitan Shanghai from the late 1920s to the

early 1950s. Willens was born to Russian Jewish parents, both

denationalized by the Soviet Union after fleeing the Bolshevik

revolution, hence her "stateless" status refers to her family's

inability to flee elsewhere. Willens not only lived through the rise of

Japanese power in, and eventual occupation of, Shanghai, but more

unique, her nationality status left her stranded in the city through the

early years of the People's Republic of China.

我發完這篇博文,就去畫畫, 畫完畫, 正剝個橘子吃的時候忽然覺得不對。等等,首先這個老太太不像翟東升所說那樣一口京片子。她從小生長在上海,不太可能說的是一口京片子,上海話是可能的。即使在北京生活過的外地人怕也難以說出一口京片子。而且在她的回憶中,家人是不允許她學說中國話的,因為沒有這種必要,家裡雇的中國傭人在當時必須跟主人說一樣的語言, 哪怕說的磕磕巴巴的。她的書是用英文寫的。我只是看了上面摘錄的段落得出這個印象,她也只會幾句上海話。 不知網友們有何其他想法?是不是另有其人?

|