(谁才是美国/世界最大的经济罪犯?为什么美国政府特意不将他们绳之以法?奥巴马虽然似乎是平民出身,说到底是美国政治生态中的一个政客。看看这个分析,很清楚地解释了他是怎样让这些最大的罪犯毫发无损,更无意改变这个罪恶的系统。 资本主义很可能是自己的终结者。)

A veteran bank regulator lays bare how Washington and Wall Street are joined in a culture of corruption.

相关阅读:

Going Easy on Eric Holder’s Wall Street Inaction

October 1, 2014

by Ryan Chittum

Attorney

General Eric Holder, left, with Assistant Attorney General Lanny Breuer

during a news conference at the Department of Justice in Washington,

Wednesday, Dec. 16, 2009. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

This post first appeared at Columbia Journalism Review.

There’s one word missing in too many major press accounts of Eric Holder’s tenure as Obama’s only attorney general: bankers.

It’s a baffling lapse for outlets like the Washington Post, Bloomberg, NPR, the Los Angeles Times, CNN and ABC News,

none of which, in their main stories on the resignation, mentions

Holder’s dismal record prosecuting Wall Street fraud in the wake of the

biggest financial disaster since the Great Depression. The New York Times drops one line toward the bottom of its front-page story on the news, inaccurately calling

it a “liberal” notion that the AG “should have used his power to

prosecute those responsible for the financial crisis in 2008.”

Holder

leaves office having been far outclassed by the Bush administration

even in prosecuting corporate criminals, despite overseeing the

aftermath of one of the biggest orgies of financial corruption in history.

In March 2009, a month after Holder was sworn in as attorney general, The New York Times reported that

“federal and state investigators are preparing for a surge of

prosecutions of financial fraud” and that the DOJ considered it a “a top

priority.”

Holder came from the white-shoe DC law firm Covington & Burling, which represented half

of the top 10 mortgage servicers, along with MERS, the mortgage records

system that played a big role in the foreclosure fraud scandal (the

firm and the Justice Department declined to tell Reuters in 2012 whether

Holder worked on any of those cases). He brought along his Covington

colleague Lanny Breuer as enforcement chief, and Breuer would play a key role in the lack of indictments of major executives.

By

the end of 2010, it was clear the financial prosecution surge hadn’t

happened, and the media began making noise about it. Holder announced

the results of a financial fraud task force, claiming more than 300

scalps.

The press quickly exposed Holder’s campaign as a public relations stunt,

reporting that many cases were started years earlier by the Bush

administration, other were double-counted, and that almost all of the

rest were small fry. Even The New York Times’s Andrew Ross Sorkin, who’s no anti-bank populist, mocked Holder’s financial fraud task force as an exercise in missing the point.

Two

years later, Holder did it again, announcing a mortgage fraud sweep had

resulted in 530 prosecutions and a billion dollars in fines. Bloomberg

immediately noticed that the DOJ had again included Bush-era cases in its tally. Several months later, the administration quietly admitted it had inflated the real numbers, which were 107 prosecutions and $95 million in fines — almost all from small-time criminals.

Then there’s the Holder Doctrine, set forth in a 1999 memo when

he was Clinton’s deputy attorney general. It says that prosecutors

should take “collateral consequences” into account when “conducting an

investigation, determining whether to bring charges and negotiating plea

agreements.”

By 2012, Breuer all but admitted that the

administration didn’t criminally charge banks because it worried about

the collateral consequences. “In my conference room, over the years, I

have heard sober predictions that a company or bank might fail if we

indict, that innocent employees could lose their jobs, that entire

industries may be affected and even that global markets will feel the

effects,” he said.

“Those are the kinds of considerations in

white-collar crime cases that literally keep me up at night, and which

must play a role in responsible enforcement.”

We know now — too

late to do anything about it — that Holder never even really tried to

investigate the banks. By early last year, 60 Minutes was confronting Breuer with reporting that

sources inside the DOJ’s criminal division who said, “There were no

subpoenas, no document reviews, no wiretaps” of Wall Street for the

financial crisis. Eventually, after the political pressure grew

intolerable, Holder squeezed billions of dollars in civil penalties from

Wall Street without forcing a single individual to face trial. Contrast

that with the Holder DOJ’s aggressive criminal prosecution of insider

trading, which is basically a Wall Street-on-Wall Street crime.

Holder

and Breuer were part of a pattern within the Obama administration of

weak Wall Street enforcement — one that leads right back to the

president himself. The tally of top officials who were close to Wall

Street and have since left for finance or finance-related jobs includes

former Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner, former SEC chairwoman Mary Schapiro, Breuer, former SEC enforcement chief Robert Khuzami, and, soon, you can bet, Eric Holder.

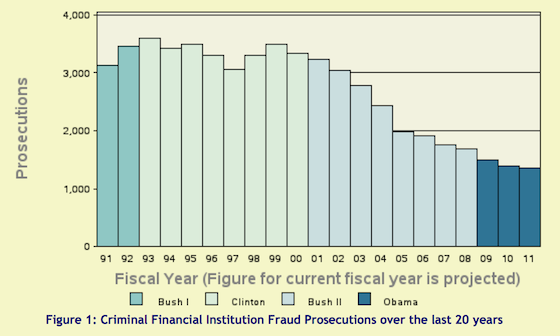

Here’s Holder’s legacy on the financial fraud front, which was one of the biggest issues he faced when taking office:

|