Protesters demonstrate against President Trump’s travel ban outside the U.S. Supreme Court in June. WIN MCNAMEE / GETTY IMAGES

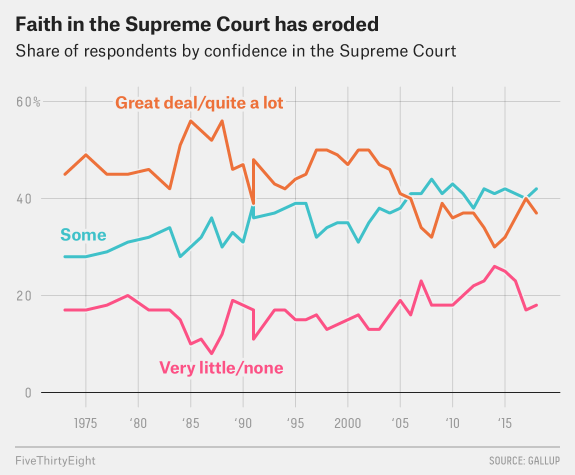

In his testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Thursday, Brett Kavanaugh dropped the demeanor of a neutral jurist and launched into a deeply partisan speech. The use of such nakedly political rhetoric during a Supreme Court confirmation hearing is highly unusual. Of course, they were unusual circumstances. Would-be justices typically present themselves as politically disinterested arbiters of law, and strenuously avoid saying anything that would pigeonhole them on hot-button issues. Now, if Kavanaugh is confirmed to the bench — and perhaps even if he isn’t — some commentators are questioning whether the Supreme Court is heading towards a crisis of faith. If confirmed, will Kavanaugh be forever marked as a political operative? And if he’s not, has his confirmation process shattered the notion that the court is truly independent from politics? I can’t say for sure whether the Supreme Court is on the edge of a legitimacy crisis, of course — it has recovered from moments of potential partisan taint before. But it’s in a weaker position now than at nearly any point in modern history. Americans, in general, have more trust in the Supreme Court than in other political institutions. But confidence in the court has been declining over the past 30 years.

Polling from Gallup, which tracks Americans’ confidence in a wide range of institutions, shows that the public has slowly become more disillusioned with the Supreme Court over the past few decades. In the 1980s, majorities routinely reported that they had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the court. Gallup’s latest polling from earlier this year, though, found that only 37 percent had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence. Meanwhile, the same fault lines that are dividing American politics also appear in perceptions of the court. A Gallup poll released last week shows that women’s approval of the Supreme Court has dropped 6 percentage points in the past year, resulting in a 17-point gender gap. It’s possible, of course, that the decline in support for the court is just a symptom of the country’s growing distrust of institutions overall. But independent of that broader trend, it’s clear that partisan tensions around the court have increased significantly as well. In the 1970s and 1980s, Supreme Court nominees were routinely confirmed with the votes of the vast majority of senators. As recently as 2005, 78 senators voted to confirm Chief Justice John Roberts.

Supreme Court confirmation votes in the U.S. SenateYEAR

| NOMINEE | YES | NO |

| 2017 | Neil M. Gorsuch | 54 | 45 | 2010 | Elena Kagan | 63 | 37 | 2009 | Sonia Sotomayor | 68 | 31 | 2005 | Samuel A. Alito, Jr. | 58 | 42 | 2005 | John G. Roberts, Jr.* | 78 | 22 | 1994 | Stephen G. Breyer | 87 | 9 | 1993 | Ruth Bader Ginsburg | 96 | 3 | 1991 | Clarence Thomas | 52 | 48 | 1990 | David H. Souter | 90 | 9 | 1987 | Anthony M. Kennedy | 97 | 0 | 1987 | Robert H. Bork | 42 | 58 | 1986 | Antonin Scalia | 98 | 0 | 1986 | William H. Rehnquist* | 65 | 33 | 1981 | Sandra Day O’Connor | 99 | 0 | 1975 | John Paul Stevens | 98 | 0 |

Since then, though, the nominees have grown significantly more divisive, culminating with the narrow confirmation of Justice Neil Gorsuch, who received only 54 votes last year. The rancor around Gorsuch’s nomination was, of course, amplified by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s decision to block the confirmation of Merrick Garland, then-President Barack Obama’s selection to fill the seat vacated by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, leaving Democrats deeply embittered about the process. It’s difficult to say that these rising tensions have caused the decline in the Supreme Court’s favorability, but they have certainly stripped the nomination process of any pretense that potential Supreme Court justices’ political views are secondary to their qualifications as judges or legal scholars. Meanwhile, the court itself has moved right under Roberts even without having a strong conservative majority, which means the addition of Kavanaugh or another Trump appointee could result in opinions that are significantly to the right of mainstream public opinion. That being said, the Supreme Court has weathered serious controversies before — including episodes that are quite similar to what we’ve seen with Kavanaugh. In 1991, Clarence Thomas’s nomination process was brought to a screeching halt by sexual harassment allegations from law professor Anita Hill, who was called before the Senate to testify. Thomas was eventually confirmed to the court, where he continues to serve as an associate justice. The country was deeply divided about the hearings and the outcome, and the percentage of Americans who said they had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the court slipped from 48 percent in February 1991 to 39 percent in October 1991. It took several years for public opinion to recover, but it was back at 50 percent in 1997. Surprisingly, there was no dip in confidence after the court’s ruling in Bush v. Gore in 2000, when the justices voted to end a recount in Florida, effectively deciding the presidential election in favor of George W. Bush. At the time, it seemed possible that the vote — which pitted five conservative-leaning justices against four liberals — would create an indelible impressionof the court as a partisan body. But 50 percent of Americans still said they had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the court in 2001 — an increase of 2 percentage points over the year before.

These episodes might suggest that the court is fully capable of recovering from the unfolding political firestorm over Kavanaugh, even if he is eventually confirmed and takes his seat as the ninth justice. But they also may have helped drive its long-term decline. The reality is that today, Americans’ confidence in the Supreme Court is weaker than it was 20 years ago. Americans may no longer be willing to give the court the benefit of the doubt. And because Kavanaugh’s appointment to the court (or that of any otherTrump nominee) would cement a five-justice conservative majority for the first time in decades, the stakes of this fight are extremely high. If Kavanaugh joins the court’s other four conservatives and begins issuing right-leaning rulings — as we have every reason to believe they would do — it’s not hard to imagine that confidence, particularly on the left, slipping even further. Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux is a writer and reporter living in Chicago. Oliver Roeder is a senior writer for FiveThirtyEight.

|